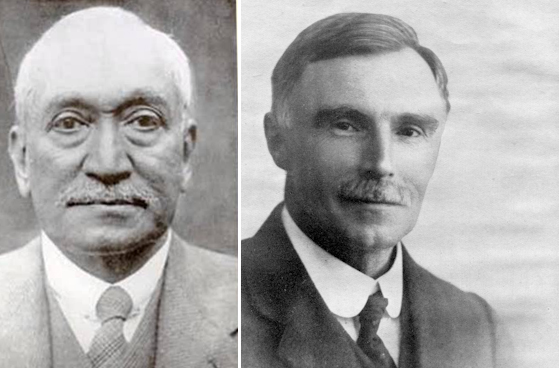

(L-R) Abdullah Yusuf Ali, (1872 – 1953) Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall (1875 – 1936)- (Photo Creative Commons)

Jamil Sherif

The Muslim socio-political activists based in London were taken aback when it became clear around 1916-17 that Palestine was under threat. Of course, there was an awareness that the strategic aim of the Western powers was to dismember the Ottoman Empire, but the fate of the Levant and Palestine was not yet on the radar.

The British interest in Palestine could have been perceived decades earlier, notably when Britain seized the opportunity to acquire a stake in the Suez Canal, only possible because of an overnight advance to HMG by Nathaniel Rothschild. This episode is well described by Lorenzo Kamel in his recently published Imperial Perceptions of Palestine.

Control of the Suez was essential to maintain the grip on India, the crown jewel of the Empire, which in turn required hegemony over the regions around the Suez, not just Egypt, but also the Southern Levant. Another, clearer signal could have been the Zionist lobby during the 1900 parliamentary election, when the English Zionist Federation sent a letter to all candidates asking for their overt support for the Zionist cause.

Lorenzo Kamel also notes the efforts of Chaim Weizmann in Manchester [Head of the Zionist Organization who later became Israel’s first President], during the 1905-6 general election, to brief Arthur Balfour, MP for Manchester East and Conservative Leader, of his vision for a Jewish national home.

Almost as soon as the Great War started in 1914, the Zionist lobby had a memorandum ready for Prime Minister Asquith regarding the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine – so the ground for the fateful Balfour Declaration in November 1917 was well-prepared.

The Muslim population in London at the time comprised the Lascars (merchant seamen), either on shore awaiting sign up or who had married locally and settled down, students often from British India enrolled at one of the Inns of Court and a handful of retired civil servants. Thanks to the budding lawyers, there were organisational efforts from the outset, with the Anjuman-I-Islam founded in London in 1886, “to promote social intercourse and the furtherance of mutual amity among the Moslems residing in the United Kingdom”. In 1903 it was renamed the Pan-Islamic Society of London, and adopted broader aims, for example, “to remove misconceptions prevailing among non-Muslims regarding Islam and Musulman” and “to render legitimate assistance to the best of its ability to any Muslim requiring it in any part of the world”.

Perhaps there were around 5,000 Muslim Londoners in the early 1900s, enough for the Pan-Islamic Society of London to organise “open air meetings” in Leicester Square Gardens and Peckam Rye. The activists in London were preoccupied either pressing Whitehall for political reform in British India or defending the Ottoman cause in intensely Turcophobic times.

The indefatigable Syed Ameer Ali, who had settled in England on his retirement from judicial service in Bengal, founded the London Mosque Fund in 1910 and the British Red Crescent Society a year later, to provide medical missions to aid the Ottomans under attack from Bulgaria and Serbia that year, “undeterred by the lack of official [British Government] response”, as noted by Professor Humayun Ansari in The Infidel Within. Palestine was not on the radar.

It fell on the astute and well-informed friend of the Ottomans, Marmaduke Pickthall, to raise the first alarm bells regarding Palestine in February 1915, much to the Establishment’s chagrin, when he had a hunch of the discussions going on between Sykes and Picot:

“Our unknown rulers seem, so far as I can learn, to contemplate a full partition of the Turkish Empire….England will have southern Mesopotamia and probably all the territory southward roughly of a line drawn on the map from a point little north of Samara on the Tigris to a point a little south of Jaffa on the coast of Palestine. The whole peninsula of Arabia would be included in her ‘sphere of influence’ for gradual absorption. France will have much of Syria.”

On July 9, 1917, the Central Islamic Society (previously the Pan-Islamic Society of London) organised a meeting at Caxton Hall in Holborn to voice concerns over Palestine. The CIS was led by an Indian student at the Bar, Mushir Husain Kidwai, and also the businessman and philanthropist of Islamic causes, Nazimuttujar Haji M. Hashim Ispahani. Pickhtall was the chief speaker – this was a few months prior to his public announcement of embracing Islam:

“I should regard it as a disaster if that country [Palestine] should be taken from the Muslim government. Must even that sacred ground be exploited by the profiteer? Must cinema places and cafés-chantants be established in Jerusalem and harlots walk the Via Dolorasa? The Muslims have preserved Jerusalem as a holy city; Palestine is a holy country, with all reverence. Would modern Christians, modern Jews, have done the like…if you want to have a new and terrible storm-centre for the world, hand over Palestine to any Christian Power…the state of things will be made worse by conquest, rousing ambitions where the population is so mixed. Among the recent Jewish immigrants into Palestine – the Jews of the Zionist movement as distinct from the native Jews – there is an extreme and narrow fanaticism which their enlightened co-religionists in Europe hardly, I think, realise. They hate the Christian and they hate the Muslim: and their supremacy would mean oppression for the other elements of the population. Their avowed intention is to get possession of the Rock (the so-called Mosque of Omar) and the Mosque El Aksa, which is the second Holy Place of El Islam – because it was the site of their Temple…”

Following the Great War, Britain and France were able to legitimise their control over former Ottoman Arab provinces through resolutions of the Paris Peace Conferences and the League of Nations. The author and journalist David Cronin, based on meticulous archival research, describes how the appointment of the British politician Herbert Samuel as first Chief Commissioner of Palestine ‘met with consternation, despondency and exasperation among Muslims and Christians, who were convinced that Samuel would be a partisan Zionist and that he represents a Jewish and not a British government ‘. A ‘Jewish Agency’ was officially endorsed, which would work with the mandate authorities ‘to encourage the close settlement by Jews on the land’. Even for the Zionist sympathiser Ronald Storrs, first military governor and the then civil governor of Jerusalem, ‘thinking Arabs’ would regard this as a colonisation, much ‘as Englishmen would regard instructions from a German conqueror for the settlement and development of the Duchy of Cornwall, of our Downs, commons and golf courses, not by Germans, but by Italians, “returning” as Roman legionaries’.

Haji Ispahani and colleagues established an Islamic Information Bureau in 1920, based at 25 Ebury Street SW1, which published a bulletin dealing with issues confronting the Muslim world, entitled the Muslim Outlook (later The Islamic News and The Muslim Standard), edited by Pickthall before he departed for Bombay in 1920. Most of the coverage was to do with Greek atrocities in Turkey, the Indian Khilafatist campaign and the terms of the Peace Conferences, but readers were not allowed to forget Palestine. The Arab Muslim leadership had betrayed their Palestinian brethren, but at least the London activists were now under no illusions of the dangers ahead,

Haji Ispahani and colleagues established an Islamic Information Bureau in 1920, based at 25 Ebury Street SW1, which published a bulletin dealing with issues confronting the Muslim world, entitled the Muslim Outlook (later The Islamic News and The Muslim Standard), edited by Pickthall before he departed for Bombay in 1920. Most of the coverage was to do with Greek atrocities in Turkey, the Indian Khilafatist campaign and the terms of the Peace Conferences, but readers were not allowed to forget Palestine. The Arab Muslim leadership had betrayed their Palestinian brethren, but at least the London activists were now under no illusions of the dangers ahead,

“May 12, 1921 – . . . Turkish rule was not very unpopular in Palestine before the war. The Turks were always ready to offer posts in their Civil Service to the sons of the best-known Arab notables of Palestine, and the municipalities were in Arab hands . . . the landowners dislike selling land to the Zionist, but in the future, as in the past, the embarrassed Muslim squire will be unable to refuse a good offer made by a Zionist . . . The Arabs, who form at least 85 per cent of the population of Palestine, object not unnaturally to hearing their country called Arez YIsrael – “The Land of Israel”. To speak before Muslims, as some young zealots have done, of the rebuilding of Solomon’s Temple on the site now occupied by the Mosque of Omar is criminally foolish . . .

“June 9, 1921, reproducing a letter to the Editor of the Times from Mushir Hussain Kidwai – For centuries past there was perfect peace in that land which is sacred to three peoples, but most of all to Muslims who cherish the relics of all the Biblical Prophets besides those of their own faith. That peace has been destroyed since the occupation of the land by the British and the adoption of the Zionist programme. Obviously, it is the Jews of Mr Jabotinsky’s type [referring to a prominent hard-line Zionist and later ideologue for the Irgun militia], who urge forming Jewish armies who have misunderstood the Balfour Declaration. To found a national home for the Jews is different from allowing the aggressive and self-aggrandising ambitions of Zionists to have a full play at the expense of the people of other faiths who have possessed the lands and properties for the last thirteen centuries and even more . . . the same sentiments of attachment to the Holy Land run today in the hearts of Muslims all over the world which was in the heart of Salahuddin (Saladin). They will never tolerate any forced occupation of Palestine by the Jews or any other people. But this does not mean that they will be intolerant to other creeds and peoples . . . Muslim territories have been a home and refuge for the Jews since the time of their persecution in Spain. In Palestine itself, Jews have numerous autonomous communities . . . Pan-Judaism or Zionism should have no encouragement if Pan-Islamism has none at the hands of Great Britain.”

Winston Churchill upheld the Zionist cause and treated the Arab demands like those of a negligible opposition to be put off by a few political phrases and treated like children’. visiting Palestine as Colonial Secretary in 1921 he ‘rhapsodised about the “smiling orchids” in the Jewish settlement of Rishon Lezion, [and] he depicted indigenous Palestinians as backwards’. Cronin also quotes the opinion of a British army, ‘the Arab population has come to regard the Zionists with hatred and the British with resentment’. The British policy of appointing Zionist sympathisers to oversee the mandate and the actions of Jewish landowners to discriminate against Palestinian labourers in May 1921 prompted what was perhaps the first Palestinian demonstration with the loss of life.

During the 1930s, London’s socio-political activists worked mainly through the London Mosque Fund and the Muslim Society of Great Britain and from 1934 the Jamiat Muslimin, based in the East End. A number of broad-based coalitions to uphold justice in Palestine emerged in this period. The Chair of Trustees of the East London Mosque Fund, Lord Lamington, for example, chaired a meeting at the Hyde Park Hotel in July 1931, “under the auspices of the National League to express its friendship for a policy of fair play and justice in Palestine”. Speakers included Waris Ameer Ali, also a trustee of East London Mosque in the footsteps of his father, Syed Ameer Ali. An account describes the event, quoting the MP, Howard Bury:

“. . . all governments, Conservative as well as Labour, were to blame for injustices to the Arabs. Members of Parliament could not get at the truth. More courage was needed . . . the difference between Weizmann and Jabotinsky was that the former wanted to lay the foundation stone, while the latter wanted the State immediately, and that if at the next [forthcoming general] election the Conservatives should win, and Colonel Amery and Major Ormsby Gore should administer the Colonial Office, his party would have to change their Palestine policy, otherwise there might be a split in the Conservative Party.”

It was a policy rapidly leading to conflict, misery, and a series of ‘Arab Revolts’ from 1936. Prominent Palestinian leaders were banished to the Seychelles, while others sought asylum in Syria and Iraq. The Black and Tans – responsible for atrocities during Ireland’s war of independence a decade earlier – was redeployed and it dealt with Palestinian opposition in a similarly brutal way. Cronin records how the Whitehall mandarins resorted to black propaganda and ‘sugar coating’ the news, ‘rather than recognising that they were encountering resistance of an inherently political nature, the British portrayed that resistance as criminal . . . the British public was kept in the dark about the revolt. Rather than holding the powerful to account, the BBC facilitated censorship of its content . . . The censorship became more stringent as the revolt continued . . . the Foreign Office was perturbed at how newsreel depicting demolitions in Palestine was being shown in German and Italian cinemas, thereby “creating an unfavourable impression”.’

Twenty years after the Balfour Declaration, the Muslim Society of Great Britain, based in a flat in the salubrious environs of Eccleston Square in Pimlico, organised a ‘Palestine Public Meeting’ in November 1937, again at Caxton Hall, chaired by Sir Edward Beaumont. The following resolution was put:

“This public meeting, representing Muslims of all nationalities in the British Empire and other lands, held under the auspices of the Muslim Society of Great Britain, is of the considered opinion that the Balfour Declaration, as it stands, is in direct contravention of the solemn pledges given to the Arabs during the Great War and urges the British Government to secure its annulment; regards the present disquieting situation in Palestine as a result of the ill-advised policy of the Government in ignoring the just grievances and aspirations of the Arabs; is grieved to find that, on account of this persistently mistaken policy, the British people are fast losing the valuable sympathy and friendship of the Muslim world; views with deep concern and apprehension any partition of Palestine, and the transference in that country of the Holy Places from Muslim to non-Muslim control; and urges the Zionist leaders and the British Government, in the interests of all concerned, including the Jews themselves, to appease the bitter feelings, and the just indignation and resentment of the Arabs by all possible means and without further delay.”

A prominent Muslim personality of the times and soon-to-be-famous Qur’anic scholar, Abdullah Yusuf Ali, was also called on to speak at similar solidarity meetings that year. While on leave from his duties as Principal of Islamia College in Lahore he would stay at his family home by Wimbledon Common, giving his time to Muslim causes. In his case events in Palestine marked a sense of disappointment and disillusionment, because an Empire he had trusted was not following the due process of law. At venues such as the Near and Middle East Association in London, he would present a carefully argued case with the skill of a barrister. He deplored the steps taken against the Arab revolt, such as the introduction of ‘Star Chamber’ methods, the alteration of the law to allow the validity of uncorroborated evidence and the ban on the Mufti of Jerusalem. He based his case on the terms of the mandates and first-hand knowledge of the circumstances of the Paris Peace Conference. His expositions commenced with an explanation that the League of Nations did not give the country holding the mandates – Britain, in the case of Palestine – any proprietary rights such as partitioning the land as proposed by the Peel Commission:

“Palestine was held under an ‘A’ mandate, which had been specially framed with the idea that the people in the mandated country were equally civilised, but is, in this case, a broken-off section of the Turkish Empire, they were in need of governmental experience. But this was only until they could stand on their own legs. The mandatory’s duty was to advise and prepare them for self-administration. They were an independent people. Both Iraq and Syria, held under similar mandates, had their independence recognised so why not Palestine. Lord Balfour went out of his way to say that England would use her influence to enable the Jewish people to have a home in Palestine provided that the rights of the non-Jewish people were in no way affected.”

Another meticulous commentator was Sir John Woodhead, who headed a ‘technical commission’ charged with assessing the Peel plan. His report on Palestine, published in 1938, contained Pickthall-like forebodings of the troubles arising:

“. . . the experiment, which the original framers of the Balfour Declaration must surely have had in mind, [was] of seeking to build up, by the joint efforts of both Arabs and Jews, a single state in which the two races may ultimately learn to live and work together as fellow-citizens . . . [but] It is not enough to rely upon generalities such as the words of the Balfour Declaration: the Arabs must be told in precise and unequivocal terms exactly what safeguards are proposed in order to protect them in future from the economic domination of the Jews . . . But the time must come when the whole of the Mandated Territories will have to be closed to Jewish immigration, and it must be clearly understood that when this time has come all obligations of His Majesty’s Government arising out of the Balfour Declaration will have been fully discharged.”

Woodhead was particularly scathing on the Peel Commission’s proposal for the envisaged Jewish state to include Galilee, where 92 per cent of the population had been Arab in the early 1920s. This would have entailed their mass expulsion! Woodhead dealt with the matter at length, concluding, ‘we are of the opinion that Galilee should not be included in the Jewish State . . . we see no justification for using force to compel this large body of Arabs in what is purely an Arab area to accept Jewish rule’. Unlike many others in the British elite, concepts like the rule of law and justice mattered to an honourable man. Woodhead subsequently accepted the honorary post of treasurer of the London Mosque Fund, which he fulfilled in exemplary fashion, while also mentoring a generation of community activists in the Jamiat Muslimin, such as the young import-export businessman, Sulaiman Jetha, who had settled in London in 1933. In March 1939, the Jamiat held a reception at the indispensable Caxton Hall, for delegates attending the Palestine Conference in London convened by the Government. The address of welcome for the Jamiat was read out by one Muhammad Baqir, a researcher at the University of London, “. . . [We] pray that God Almighty help them [the delegates] to realise the hope of their Palestinian brethren”.

It must have been a memorable event with its variety of attendees: Palestinian leaders like Amin Tamimi and Jamal Husseini; Prince Faisal Ibn Abdul Aziz and the Saudi Ambassador in London, Shaikh Hafiz Wahba; Choudhry Khaliquzzaman, the Muslim League leader from United Provinces, British India; trustees of the London Mosque Fund, Lord Lamington and Waris Ali, the latter now an informal advisor to Winston Churchill on Indian Muslim affairs. Also present were a number of Muslim students and the Jamiat’s office-bearers, secretaries Ahmed Din and Ghulam Muhammad, and President Dr Muhammad Baksh. A Jamiat report on the occasion notes, “Mr A. R. Siddiqi (Member Legislative Assembly, Bengal) also thanked the Association [Jamiat Muslimin] for their welcome and voiced the sentiments of Indian Muslims about the present situation in Palestine”.

Alas, the London Conference did not achieve much, hampered by a lack of unity within the Muslim negotiating team and Ben Gurion’s intransigence in pressing Zionist demands. World attention was also distracted by Hitler’s army entering Czechoslovakia. The British troops still in Palestine at the end of the War were now subject to terrorist attacks, such as the King David Hotel bombing, by Irgun who also commenced ethnic cleansing of Palestinian villages. The Holocaust had changed perceptions in the West and there was an unwillingness to challenge Jewish migration from Europe or Israel’s self-declaration as an independent state in 1948.

Balfour’s legacy is thus one of injustice and turmoil. The need to keep an activism for Palestine in London and elsewhere remains, with no dearth of inspiring examples to draw on from the past.

Further reading/references

Balfour’s Shadow, A Century of British Support for Zionism and Israel by David Cronin, Pluto Press, 2017

The Infidel Within, Muslims in Britain since 1800 by Humayun Ansari, Hurst & Company, 2004 – a comprehensive account of Muslim settlement and institution building

Woodhead Commission, Palestine Partition Commission Report, Command Paper 5854, 1938 – for criticisms of the partitioning proposals made by Peel.