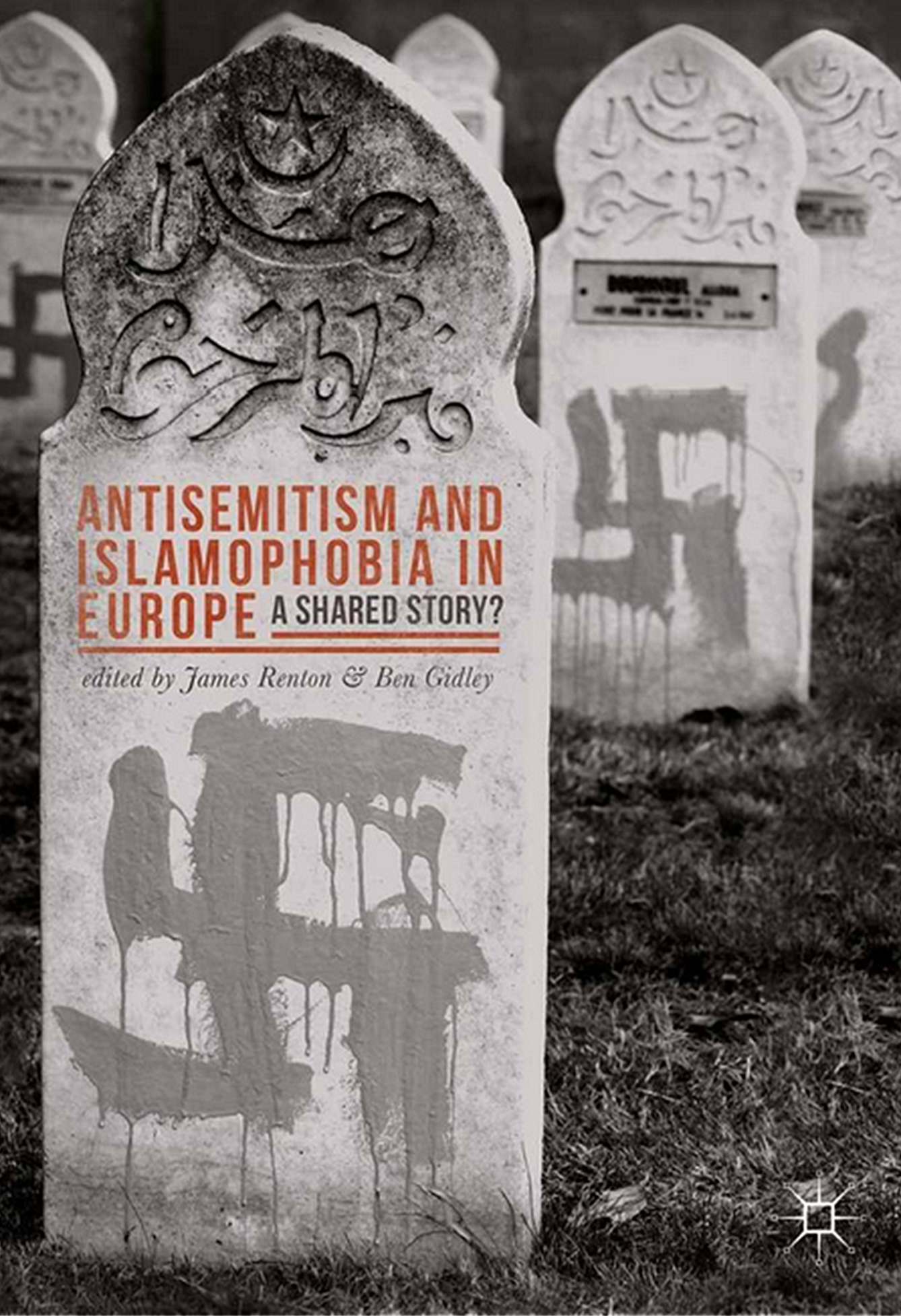

Antisemitism and Islamophobia in Europe: a shared story?

Editors: James Renton and Ben Gidley. 2017. Palgrave MacMillan. Paperback £19.99

The intricacies of the relationship between these particular types of racism are well reflected in the vast time-frames and varying approaches covered in this book. We see how the trajectories of antisemitism and Islamophobia are not opposing as Middle East war propagandists like to assert, nor are the trajectories completely parallel, but instead meet and diverge at different points in history, underpinned by a political context that remains the most important factor of all in shaping both antisemitism and Islamophobia in Europe.

In the introductory chapter Renton and Gidley allude to this political context going as far back as early Christendom’s territorial ambitions: “The Jewish or Muslim questions are products of a Christian Question: the racialised blood identity of Christendom- of Europe- from the time of the Crusades onwards”.

Old imperial orders

Jacques de Vitry, a historiographer of the Crusades, stated categorically in his Historia Orientalis written in the early 1220s that the Muslim sect of the Assassins (or Esseie) of Jerusalem were descendants of a Jewish sub-group called the Essenes. There is no other evidence of such a Jewish sect existing (the name itself can be traced to a Christian group in the medieval West) which has led Andrew Jotischky, author of the first chapter in this book, to argue that the two groups were conflated because they sounded alike and it was not implausible that a Jewish sect could morph into a Muslim one in the Jerusalem of the Crusades, such was the mystery shrouding these exotic new religions.

Fast forward to 16th Century modern Spain and Portugal that had sizeable Muslim and Jewish populations. In the era of the Spanish Inquisition, these religious minorities were under the spotlight and far from unknowable. In fact, the threat they posed was a direct consequence of how well they had assimilated into Iberian society. In the third chapter, Francois Soyer explores a particular incarnation of this threat in the form of a widespread conspiracy theory of Jewish doctors murdering their patients.

This theory was lent credence by the fact that Jews were over-represented in medical circles and, most importantly, by the number of Jewish converts to Christianity. It was this ability to “hide” amongst Christians whilst simultaneously having their lives in their hands that made them so suspect and dangerous. The Moors of Spain were also a threat, but a more obvious and visible one that could be targeted without conspiracy theories. The antisemitic trope of the medical murderer was so widespread that it eventually became a catch-all racist trope that was used against the Moor population too.

A similar pattern of racialisation of religious minorities can be found in 19th Century Imperialist Russia, expanded in the next chapter by Robert D Crews. This was a time of great uncertainty for imperial orders due to widespread nationalist aspirations across Europe. In the context of inter-imperial rivalry, Muslims were seen as a greater political threat, particularly along the Romanov-Ottoman border.

The Jewish population, being smaller, was treated differently through attempts at forced conversion to Orthodox Christianity. Despite the differences in the type of political threat posed, both Muslim and Jewish communities were put in the same legal category of non-Orthodox religions under Nicholas I.

With the Jewish population having a greater number of converts (due to a policy of forced conversion that specifically targeted Jews) and a greater mercantile presence, Jewish communities were subjected to specific forms of targeted harassment and violence, from Government policy that prevented Jews from changing their names after converting, to peasant-led violence and repeated pogroms that the authorities turned a blind eye to. As for Muslims, the threat they posed emanated from Russian fears of pan-Islamism.

Even remote rural Muslim populations were treated with the same level of suspicion, a type of demonisation that fuelled the local civil wars with Orthodox Christians. As Crews notes: “Rooted in the anxieties of nationhood and European modernity, anti-semitism and Islamophobia in the tsarist empire were key components of Russian nationalist ideology”. (p.93)

Neo-imperialism

The new nationalist aspirations of Europe had no place for religious minorities. During the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s, over 25,000 Ottoman Muslims may have been killed. Jews were treated in a similar fashion so that none were left in the Peloponnese by the end of the war. Curiously, however, in the nearby Balkans, the story of nationalism is very different and nationalist aspirations did not develop along religious lines

A unique phenomenon takes place in the Balkans at the turn of the 20th Century, where nationalism is played out on a smaller geographical scale, and where culture and language are the most important defining factors of national identity, rendering religious identity almost irrelevant.

In his chapter on the Balkans, Marko Atilla Hoare reveals the fascinating shift in Balkan nationalist identity over the course of a century. Once upon a time, according to the founding father of integral Croat nationalism, Ante Starčević, Bosnian Muslims were the ‘flower of the Croat nation’. Some 100 years later they were a fanatical expansionist enemy. Similarly, if you google Gligorije Jeftanović, a Bosnian Serb political leader of the late 19th Century, he is wearing a Fez to mark his Serb identity and differentiate himself from his Austro-Hungarian rulers.

During the Second World War the Communist Partisan movement of Yugoslavia united Croats, Muslims, Serbs, Jews, Orthodox and Catholics, in the fight against Nazi expansionism. The leader of the ultra-nationalist Serb Chetniks, Draža Mihailović, despite having been involved in wars with Muslim Bosniaks, went so far as to call for Sarajevo to be an Islamic spiritual centre in Europe and for Islam to be an equal state religion in Serbia in his efforts to unite Serbs.

A mere four decades later, the Serbian army massacred Muslims in Srebrenica. How did Serb nationalism go from celebrating Islam to being behind the murder of 8000 Muslims? Hoare doesn’t provide an adequate explanation for this complete attitude shift, but there are clues throughout the chapter.

Croatian Leader Franjo Tudjman said in 1997: “Neither Europe nor the United States accepted the birth of a purely Muslim entity which would favour Islamic expansion…today in Bosnia 174 mosques are being built, while Catholic churches are destroyed and only three are being restored.

There is obviously a desire that that county be Islamised”. (p.178) It is clear from this statement, although Hoare doesn’t elaborate it, that global events, especially regarding the US geopolitical position towards the Middle East and the post-communist threat of global ‘Jihadism’, influenced Balkan nationalists to such an extent that they turned on their neighbours and former allies.

In his contributing chapter to this book, James Renton explores the racial category of the “Semite” – its origins and how it was used by British Conservative MP Sir Mark Sykes as a conceptual propaganda tool when carving up of the former Ottoman empire.

The racial category of the Semite came to prominence through the work of French Philologist Ernest Renan, who helped formulate the category around the similarities between the Hebrew and Arabic languages. Sykes, therefore, had a useful academic tool to justify creating a Jewish homeland in an Arab heartland, particularly as he knew he was bringing together two very different communities and needed a means to ease that transition.

For Sykes, there were two important reasons why he needed to create a Jewish homeland, and the ready-made racial category of the Semite made his reasons all the more appealing. Sykes saw “Zionism as a well-established movement that would help to bring civilisation to the backward Holy Land”. (p.118)

The joining together of Semites was also a process of political education for “even Renan judged contemporary Jewry to be far removed from the Semitic Arab.” Just as importantly, Sykes wanted to appease the leaders of the Zionist movement because he and many others had bought into the conspiracy theory of a global network of powerful Zionists.

The consequences of the Zionist project, whether intended or not, go well beyond that particular part of the world, creating historical amnesia through which the enmity between Muslims and Jews seems timeless, and where historical Christian enmity towards these two religious minorities is almost completely forgotten. Renton and Gidley succeed, through this book, in starting to reverse that amnesia.

In their ethnographic study of British Muslims and Jews in the last chapter, Yulia Egorova and Fiaz Ahmed touch upon the origins and dissemination of this apparent so-called enmity through the British mainstream media.

In chapter 9, Daniel A Gordon explores the French antiracist movement’s response to the seemingly impossible balancing act of tackling Islamophobia and antisemitism with the same level of commitment. But it is the insightful and fascinating historical framework of the book’s previous chapters, from the Crusades to the Second World War, that provides us with the crucial context and key to not only understanding Islamophobia and antisemitism in the current political climate but to beginning to understand the future of tackling these strands of racism together.

Ala Abbas