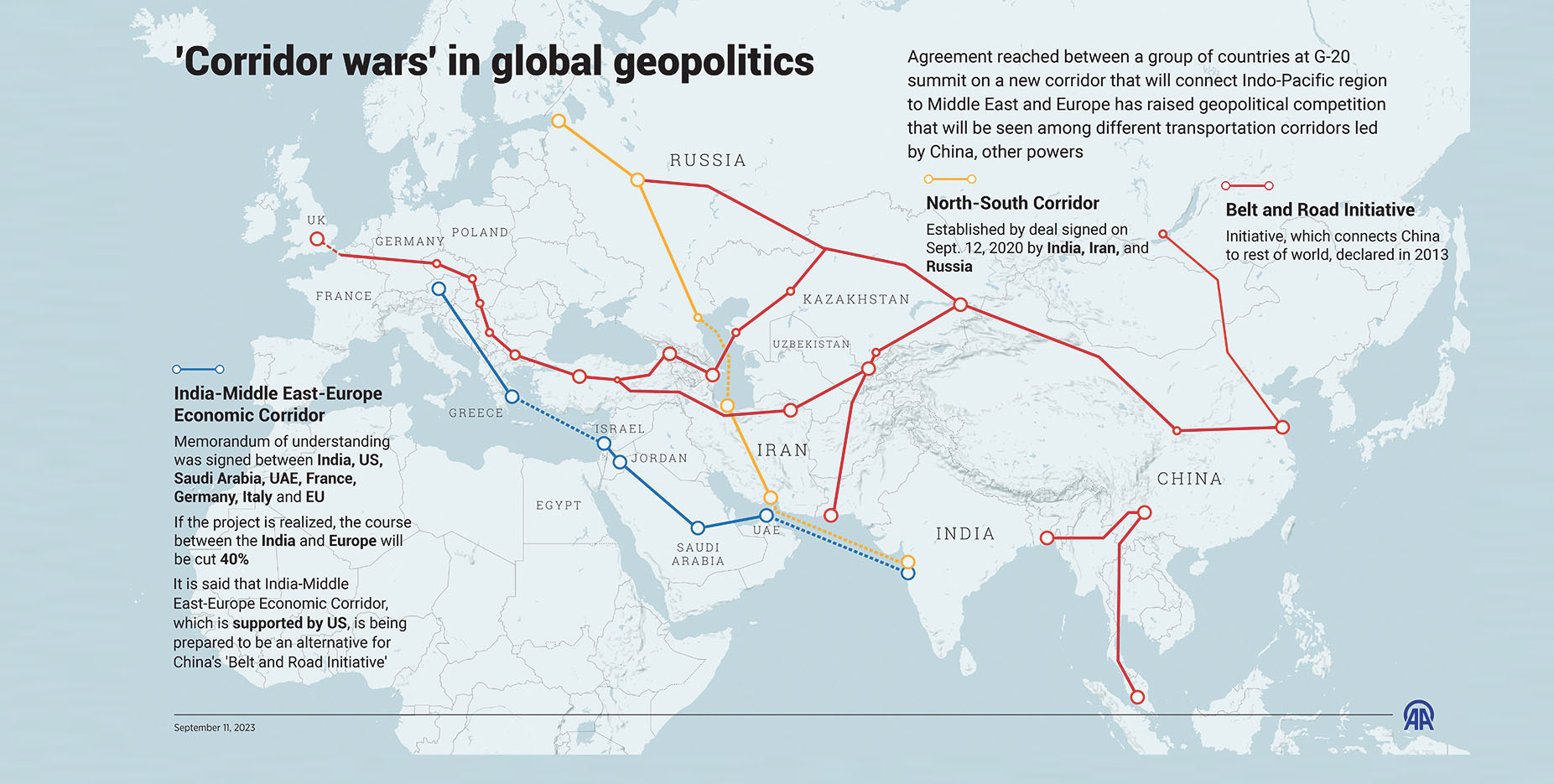

Agreement reached between countries at G20 summit on a new corridor that will connect Indio-Pacific region to Middle East and Europe has raised geopolitical competition that will be seen among different transportation corridors led by China, other powers. The G20’s “corridor” in seen as an imitation of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

(Credit: Elmurod Usubaliev/Anadolu Agency]

Senator Mushahid Hussain Chair, Senate Defence Committee

Reflecting a polarised world, two major summits within a span of three weeks, with some overlap in membership but on different continents, presented a marked contrast in goals and outcomes. The Summit of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) hosted by South Africa and the G20 Summit held in India in August and September, respectively, are contrasting examples.

The BRICS Summit in the land of Mandela reflected the late leader’s ethos of pluralism and inclusivity, while the G20 Summit in the land of Modi saw the conspicuous absence of China’s President Xi Jinping, who had been the star of the show in Johannesburg. President Putin was absent from both, while President Biden and other Western leaders were in attendance in a spruced-up New Delhi.

However, both summits were dominated by the ‘China factor’: BRICS, which had substance, was essentially showcasing Chinese diplomacy at its best because, after Beijing brokered the historic Iran-Saudi Arabia rapprochement in March, at BRICS, both these protagonists, together with the UAE plus Ethiopia, Egypt, and Argentina, were welcomed into what is now BRICS+, making the largest producers and consumers of oil sit around one table.

And at the G20 Summit in Delhi, which was more about symbolism as a two-in-one attempt by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to make India the West’s bridge to the Global South while choreographing the early launch of his own election campaign through extensive billboards, photo-ops, and not-so-sophisticated PR, the most concrete outcome was to unveil a copycat project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Despite deriding BRI, the West pushed for the launch of the grandiose-sounding India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). Imitation, as the English saying goes, is the highest form of flattery! Interestingly, IMEC did not have a smooth launch with

President Erdoğan’s open opposition and the reservations of China and Russia.

Incidentally, it is the third attempt in three years of a Western copycat project of the BRI: in 2021, President Biden announced the B3W (Build Back Better World), which was later rebranded as the Partnership for Growth in Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), while the European Union, not to be left behind, announced its own copycat version of BRI, calling it ‘Global Gateway’.

And what was touted as a ‘breakthrough achievement’ at the G20, the ‘consensus’ on Ukraine, was actually a rehash and reaffirmation of universal principles enshrined in the UN Charter and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence (200 man-hours spent on their drafting, apparently!). The real story was in the West’s retreat on Ukraine from a position of outright condemnation of Russia to acquiescence to India’s superb ‘diplomacy by deft drafting’ of verbiage in the English language!

The fundamental difference between the G20 and BRICS+ is that the G20 remains an extension of the G7 with strong geopolitical overtones and is largely a status quo platform now influenced by a Cold War mindset, of which India, as a major American ally, is a key component. Conversely, BRICS+, spearheaded by China, is both geopolitical and geoeconomic, with strategic clarity on a vision and the will to play a proactive role in a world where the Global South is the pivot. Hence, de-dollarisation forms part of the BRICS+ agenda.

The future of both BRICS+ and G20 will also be determined by their respective (stated or unstated) goals, and their contrasting visions. China, as a country with a long civilisational heritage, has been the harbinger of globalisation for the past 2,000 years, when the Silk Road connected China with Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe through commerce and culture. It is the modern-day version of the Silk Road, the BRI, now 10 years old, comprising 150 countries and 32 international bodies, with an investment of $1 trillion in 3,000 projects, generating 420,000 jobs, and lifting 40 million people out of poverty. Out of the 193 UN member states, 130 have more trade with China than with the US, from the Solomon Islands to Saudi Arabia.

Underpinning the BRI and BRICS+, for that matter, are institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank, respectively. And BRI has been reinforced by the Global Development Initiative), the Global Security Initiative, and the Global Civilisation Initiative, which promote equality, inclusivity, and diversity through connectivity and cooperation.

China is focusing on modernisation, especially cutting-edge 21st-century technologies like 5G, Artificial Intelligence, robotics, and cloud computing, according to a landmark study by Harvard University, ‘The Great Tech Rivalry: China versus the United States’. ‘China is displacing the US in hi-tech manufacturing’, as evident in the recent launch of the Huawei Mate60Pro smartphone, which has managed to beat the American sanctions by producing an advanced, sophisticated, state-of-the-art tech product.

Conversely, the past two American administrations have been busy militarising international relations, increasing their military budgets, building military bases (almost 400 in Asia alone!), arming Asian allies against China, and building a network of military alliances, including an ‘Asian NATO’, while NATO now talks of the ‘China threat’.

No wonder CNN referred to the fact that ‘China is nothing short of a foreign policy fixation in Washington,’ although Fareed Zakaria gave the correct prognosis that ‘the rest of the world doesn’t see China as we do.’

And one reason for this yawning chasm between the West and the rest on China policy is, as the former Senior American Administration official, Fiona Hill, aptly commented, that ‘the Global South sees the US as full of hubris and hypocrisy’ in the conduct of its foreign policy.

The American fixation with China can even become borderline racist. In May 2019, Kiron Skinner, Chief of Policy Planning at the US State Department, openly described the conflict with China as a ‘fight with a different civilisation’, even providing a racial context of the emerging US-China competition, saying “it’s the first time we will have a great power competitor that is not Caucasian”.

China’s leadership role in the Global South has also been enhanced by its proactive diplomacy in building bridges, as Beijing successfully became an honest broker between Iran and Saudi Arabia, ending a long-standing proxy war destabilising much of the Middle East for the past three decades.

48 years after G7 was launched in 1975, 15 years after the launch of its offshoot, G20, and 10 years after BRI was announced in 2013, their respective worldviews, policies, and approaches are rooted in their different ‘strategic cultures’, based on their historical evolution, and analyses of these are necessary for understanding these divergences.

2023 is also the year of anniversaries for both China and the US, reflecting this contrast in perspectives and policies. For China, which has an economic-centric approach, it marks 10 years of BRI, the most important developmental and diplomatic initiative of the 21st century. For the US, 2023 marks three anniversaries reflecting the US security-centric worldview: 70 years of the CIA coup in Iran, 50 years of the CIA coup in Chile, and 20 years of the war in Iraq. Their respective strategic cultures reflect this contrast.

Key components of China’s strategic culture include the Silk Road, which facilitates connectivity and cooperation among countries, cultures, and civilisations the Great Wall, which manifests China’s defensive and protective approach against outside intruders and aggressors; Long March, an epic of the Chinese Revolution that was a long and costly struggle for survival that demonstrates patience, perseverance, and persistence, and a ‘never give up’ spirit; ‘century of humiliation’ from 1840-1949, a determination of ‘never again’ allowing for violations of China’s unity, sovereignty, territorial integrity, and dignity.

China’s march to modernisation takes inspiration from its strategic culture.

Hence, it is no accident that China is the only global power in history to rise peacefully without invasion, conquest, colonisation, or aggression. Earlier this year, in March, President Xi Jinping announced the Global Civilisation Initiative, which is more about dialogue, harmony, and respect among civilisations, as opposed to the mantra about the ‘clash of civilisations’, first peddled by Harvard Professor Samuel Huntington 30 years ago.

On the contrary, the American strategic culture has key ingredients that are reflected in the US approach and worldview in the present-day era.

These include: an obsession with Pax Americana, since the days of the Monroe Doctrine, a desire to dominate; a glorified self-image of ‘American exceptionalism’, a ‘we are unique’ expression of moral superiority over others, a modern-day post-colonial version of the ‘white man’s burden’, an international do-good-er that invades & occupies countries or brings ‘regime change’ for the greater good of countries at the receiving end; a trigger-happy ‘might is right’ ‘shock & awe’ approach in foreign affairs which can rightly be termed as ‘John Wayne style’ of diplomacy which at times ‘shoots-first, asks questions later’; a powerful military-industrial-complex that is a permanent war machine which needs to be refuelled constantly by bulging military budgets and an unending quest for an ‘Enemy’.

For the foreseeable future, as these summits underline, China is embarking on presenting a strategic option to the Global South (similar to what President Charles de Gaulle was presenting to Europe at the height of the Cold War) by building an alternative, more equitable world economic and political order, reflecting the shift in the global centre of gravity from the West to the East.

Western leaders have also hinted at this transformation. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has talked of an ‘epochal tectonic change’ or ‘Zeitenwende,’ referring to a rapidly transforming global scenario. French President, Emmanuel Macron, was even more blunt, telling his diplomats that ‘to accept the fact that 300 years of Western hegemony is coming to an end’.

As regards the ‘leader of the free world’, Joe Biden, the architect of the New Cold War, an influential newspaper, The Telegraph, published from London, put it rather bluntly in its edition of September 13: ‘You are not supposed to say so in polite company, but Joe Biden is no longer fit to be President of the US.

It would be a lot better for America and for the rest of the free world were he to step down early for reasons of ill health, or at the very least not stand again for the Presidency, given Biden’s gaffes, blunders, and tragic signs of rapidly deteriorating capacity’.

With an actual war raging in Europe in Ukraine and a new Cold War in the offing in Asia, such a person as President of the US is a clear and present danger to global peace, security, and stability.