Zainab Gulamhusein

The question of how we die, and who should have the right to decide, has taken centre stage in Parliament with the Terminally Ill Adults (End-of-Life) Bill (the “Bill”).

The Bill, which would allow mentally capable adults with six months prognosis to choose a medically assisted death under strict safeguards, has sparked a deeply personal and moral debate. Moving beyond legal details, lawmakers, families, and commentators are grappling with fundamental questions about dignity, autonomy, and what it means to care for the most vulnerable at the end of life.

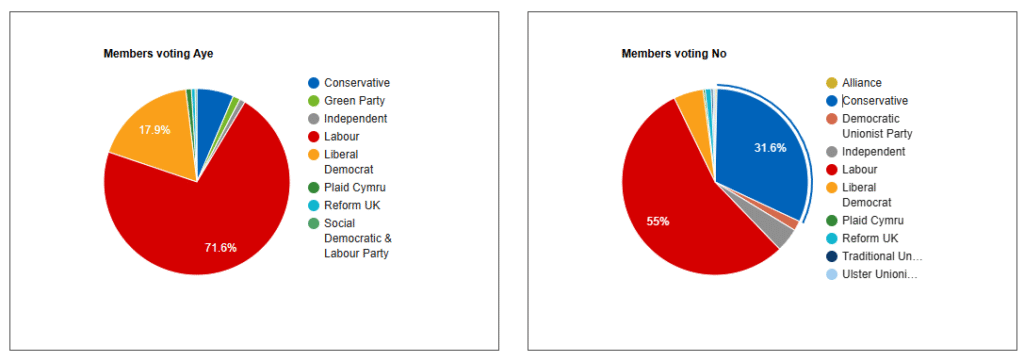

The Bill, which passed the Commons by a narrow margin of 314–291 in a free vote, appears straightforward on paper. Mentally capable adults expected to die within six months would be allowed to choose a medically assisted death, subject to multiple assessments and strict safeguards.

A small number of Muslim MPs, including Labour’s Tulip Siddiq and Sadik Al-Hassan, supported the Bill, but the majority (around 84%) voted against it. Their opposition reflected concerns not just about safeguarding, but also broader ethical questions.

Their contributions go beyond simple “religious objection,” drawing on a rich Islamic ethical tradition that considers life, death, medical duty, and human limitation in a nuanced, context-sensitive way.

Looking at individual MPs as examples, Labour’s Shabana Mahmood has emphasised her core concern, that life is inherently valuable and should not be ended through intentional human intervention. Independent MP Iqbal Mohamed stresses a moral responsibility to protect life and raises concerns about the societal implications of normalising assisted dying.

Labour’s Naz Shah highlights structural inequalities in healthcare access, warning that minority and low-income communities may face greater vulnerability. MP Shabana Mahmood’s concerns are echoed in scholarly discussions, such as Abdulaziz Sachedina’s “End-Of-Life: The Islamic View”.

Sachedina emphasises that in Islamic ethics, life is sacred and ultimately belongs to God, placing strict limits on human authority to end it. While withdrawing life-sustaining treatment is permitted in certain medically inevitable circumstances, actively causing death is prohibited.

While Shabana Mahmood’s objections are grounded in principle, Islamic law is context-sensitive, recognising the need for careful moral reasoning alongside medical judgement. Ethical deliberation, Sachedina argues, must balance respect for life with recognition of human limitations.

MPs who backed the Bill often highlighted personal autonomy, dignity, and compassion, pointing to cases of prolonged suffering as key motivators. Supporters also focus on the human stories behind the debate, describing families witnessing loved ones endure unbearable pain in their final days. They argue that the Bill provides strong safeguards, a rigorous decision-making process, and protections to minimise the risk of coercion.

Broadcaster Jonathan Dimbleby is one high-profile advocate in support of the Bill. Speaking from experience after his younger brother died from motor neurone disease, Dimbleby has described the current law as “increasingly unbearable.” He has urged MPs to legislate, emphasising that terminally ill adults of sound mind should be able to choose the timing and circumstances of their death. With strict safeguards, he argues, reform could provide dignity and reassurance for those facing unbearable decline.

Supporters also point to international examples.

Assisted dying is legal in countries including Canada, New Zealand, parts of Australia, several U.S. states, and European nations such as Switzerland, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Advocates argue that these examples show carefully regulated frameworks can work in practice. Yet, as Independent MP Iqbal Mohamed and others caution, even in a regulated system, there are wider societal implications to consider. Normalising assisted dying could subtly reshape how society understands the value of life and the duty to care for those who are struggling.

Some fear it might shift expectations around what it means to support people at the end of life, especially those who are disabled, elderly, or otherwise vulnerable. It could also place new pressures, ethical and emotional, on doctors who would be asked not only to preserve life but, in some cases, to help end it. For critics, these broader cultural and professional consequences are just as important as the legal details, and they worry about how such a shift might change our collective approach to compassion and care.

MP Naz Shah and other MPs have highlighted that legalisation alone does not guarantee genuine choice. In a country where palliative care is unevenly available, some terminally ill patients may face unnecessary pain simply because proper support is lacking. Language and cultural barriers can make it harder for some communities to navigate the system or understand their options.

Marginalised groups may also distrust healthcare providers, leaving them hesitant to request assistance even when legally permitted. For many, the “choice” to end life may be constrained by circumstances beyond their control. This shows the importance of addressing inequalities in healthcare alongside any legal reforms.

Supporters describe the Bill as a compassionate step, intended to spare people from needless suffering. Yet once the conversation moves beyond the wording of the legislation and into the realities faced by patients and families, the challenges become far more layered.

The debate ultimately touches on broader questions about how we care for one another, how we protect the most vulnerable, and where the limits of medicine should lie. Personal autonomy matters, but so does collective responsibility. Genuine compassion may require more than simply changing the law. Before altering one of the most significant boundaries in human life, that being the choice to end it, we may need to address the inequalities that determine who actually gets to make that choice.

Regardless of how the Bill fares in the House of Lords, the debate has sparked a thoughtful conversation about what it truly means to die well, and what kind of society we want to be when faced with life’s hardest decisions.

NB: At the time of writing, the Bill is moving through committee stage in the House of Lords.

(Feature photo credit: Freepik/CC)

Zainab Gulamhusein, is a lawyer.