Sarah Hussein

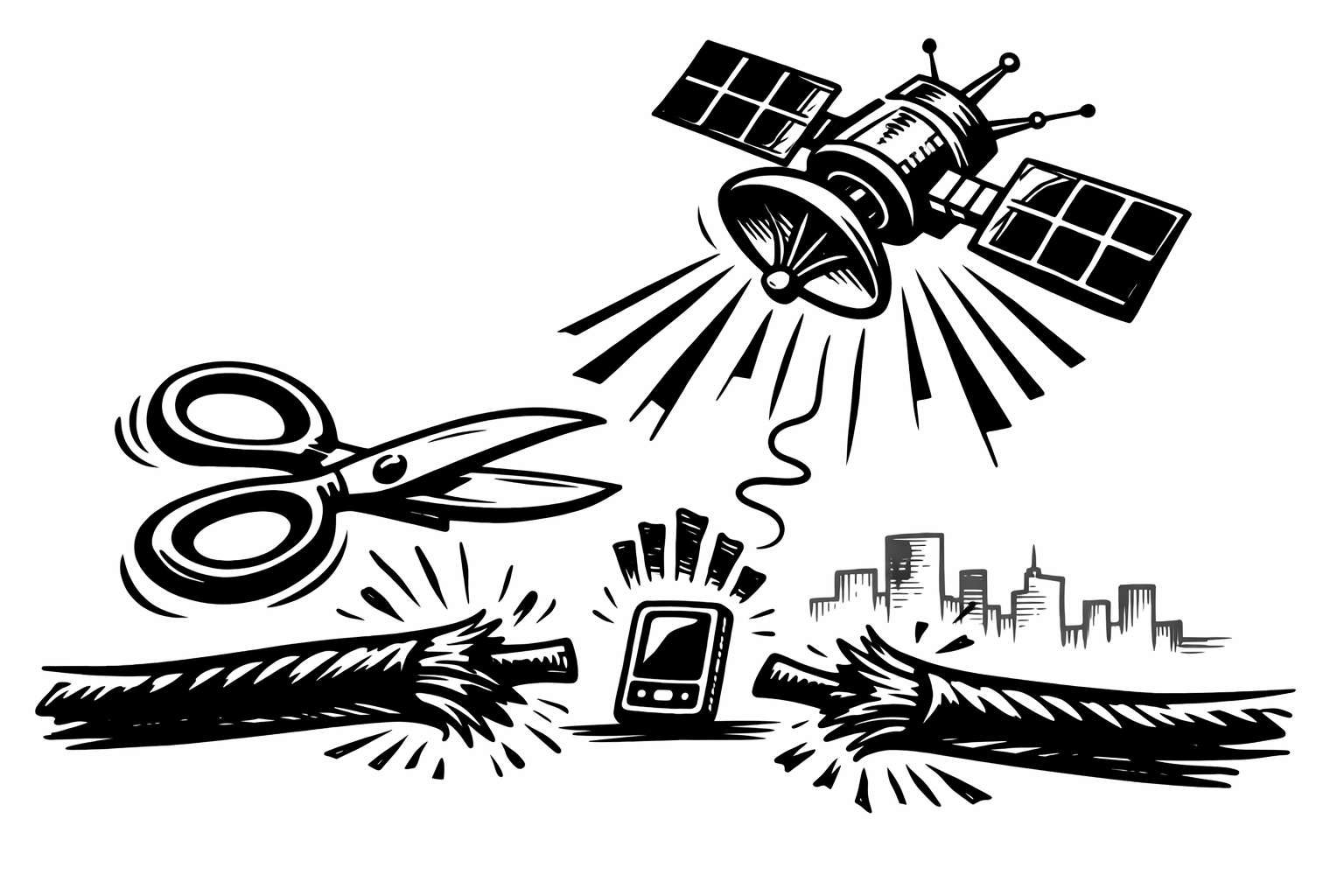

In today’s conflicts, control over information has become almost as significant as control over territory. Governments increasingly restrict internet access during unrest, cutting people off from the outside world and suppressing independent reporting. These digital blackouts, whether through network shutdowns or deliberate filtering, leave civilians unable to contact loved ones, seek help or share what is happening around them.

In this context, satellite connectivity has emerged as one of the few tools capable of bypassing national telecom systems and restoring a lifeline to the outside world.

Traditionally, satellites have supported communications, navigation and broadcasting. More recently, constellations of satellites in low Earth orbit have enabled high-speed internet access that can reach remote or cut-off regions. Starlink, a satellite internet service run by SpaceX, is one of the best-known examples, designed to deliver connectivity directly to user terminals even where local networks are non-existent or disabled.

The humanitarian and political implications of this technology are stark.

Satellites, by design, bypass national telecom infrastructure. This means that when states restrict mobile networks and fibre connections, satellite services can still provide an outlet for communication. During protests or conflict, this can allow civilians to share information, access emergency services and connect with journalists or family abroad.

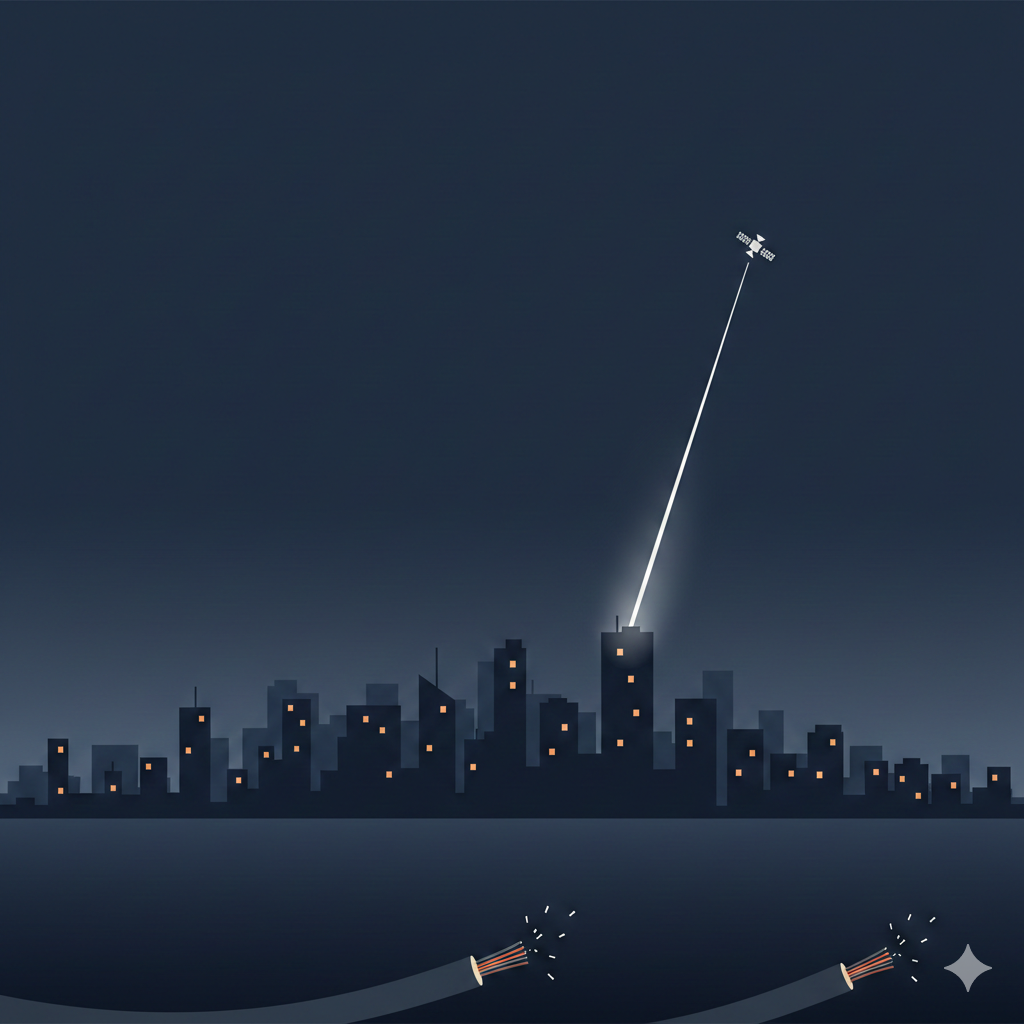

In Iran, these dynamics have played out in real time. Nationwide internet blackouts imposed in early 2026 left much of the country cut off from global connectivity, with ordinary networks disabled and only limited access available under state control. Starlink was one of the few services that initially continued to provide a connection, allowing activists and civilians to send messages and footage from within the country when traditional internet was severed.

The Iranian government, however, has resisted this new channel of connectivity. After satellite internet providers were officially banned, possessing or using Starlink equipment became illegal, and authorities have sought to intercept and confiscate terminals. Iran has deployed electronic warfare measures, including sophisticated radio-frequency jammers to disrupt satellite links and prevent receivers from locking onto signals. These tactics mirror counter-communications strategies seen in other conflicts and demonstrate how states are adapting to satellite technology’s increasing role in information flows.

Starlink terminals themselves depend on GPS signals to orient antennas towards orbiting satellites. By jamming local GPS signals, Iran has disrupted these connections, creating patchy or unreliable service and forcing some users to reposition equipment constantly to maintain an intermittent link. Authorities have also reportedly used surveillance drones to locate Starlink dishes, which must be placed outdoors with a clear view of the sky.

Satellite internet did not suddenly appear in Iran during the latest unrest. Its story began in 2022, when protests followed the death of Mahsa Amini and authorities imposed internet restrictions. Around that time, Starlink terminals quietly began entering the country — smuggled, shared and passed between communities. They were rare and expensive, but they offered something new: a connection that did not depend on the state’s networks.

Their presence was enabled by a US decision to carve out a sanctions exemption for satellite connectivity in Iran. In doing so, access to communication was framed as a civil rights concern rather than a matter of trade.

Inside the country, possession remains illegal. Once identified, equipment can be confiscated or disabled, adding a physical enforcement layer alongside electronic jamming. Some owners have also been accused of espionage. Yet the risks have not prevented their spread; thousands circulate informally, kept specifically for moments when ordinary communication disappears.

Satellite internet does more than bypass national infrastructure; it shifts trust to a private global network operating beyond local oversight. As with any internet provider, connection data — including approximate device location, activity times and traffic patterns — can be generated even when message content itself is encrypted. Because that data may pass through foreign ground stations and legal jurisdictions, questions remain about who can ultimately request or access such records. In politically sensitive environments, this creates a difficult tension: the very connection that enables people to speak can also produce traces that make them visible.

This has created a recurring pattern. Each shutdown becomes a contest between authorities attempting to close the digital space and civilians attempting to reopen it, turning satellite connectivity into a standing feature of unrest rather than a temporary workaround.

The broader significance of these developments goes beyond a single country. As satellite internet becomes more accessible, with innovations under development to connect directly to mobile phones, states are grappling with how to assert control over information without borders. Satellite networks challenge the notion that governments can completely manage digital spaces within their territory, particularly during moments of political upheaval.

Yet this shift also raises ethical and legal questions. Who controls access to the skies? What safeguards exist to protect civilian use of space-based connectivity? And how can emerging technologies be used to advance human dignity rather than merely strategic advantage?

For many around the world, especially in regions affected by conflict or systemic suppression, access to unfiltered communication is not a luxury. It is a matter of survival, justice and visibility. As satellites increasingly shape the flow of information in crises, they are emerging not just as technical infrastructure, but as instruments of human rights and resilience.

Image: Created using AI (ChatGPT)